Nonpartisan Redistricting: Citizen Commissions Drawing Districts

While 2016 was momentous, the 2020 election is arguably a bigger political event. The presidential contest coincides with the election of state legislators who control the next round of redistricting – drawing new lines for their state’s Congressional seat and their own seats for the decade to come.

While we brace for another partisan redistricting battle, we have to ask – why do partisan elected officials get to draw their own districts? How do incumbent legislators get to choose their voters before voters choose them?

It’s hard to imagine our founders envisioned a permanent system where, if one party controls both state legislative bodies and governorship, they can rig the system in their favor. Or, if the two major parties split power, they collude to gerrymander districts safe for themselves and less competitive for opponents.

Indeed as modern targeting technology has made redistricting a partisan science, there has been a steady drop in Congressional seats where the outcome is in doubt and voters have a meaningful choice. In 2014, only 39 out of 435 seats were considered competitive. 2016 was even worse. Just 37 – less than 10% – of U.S. House races were seriously contested the lowest in five decades. Safe districts limit voter choice. They fuel hyper-partisanship. Incumbents of either party need only appeal to their base. There is less incentive to broaden their message, compromise or have meaningful debates on issues.

History

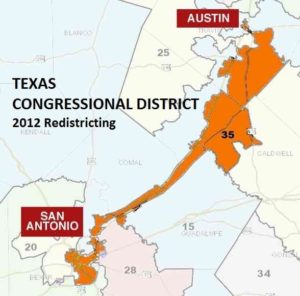

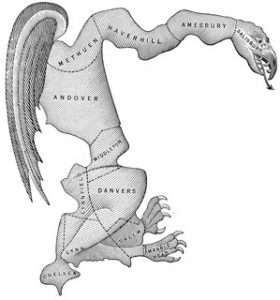

How did we get here? The United States inherited the idea of lawmakers drawing their own districts from colonial England. Population was sparse and there was no other precedent to go on. Back then, districts varied in population and followed town and county lines. Gerrymandering was born early on in 1812. Then Massachusetts Governor Gerry drew districts to advantage his party. An infamous one shaped like a salamander. The press called it a “Gerry-mander”. Rigging districts got its name and its start. Fast forward to the 1960’s when the Supreme Court required legislative districts have equal population with the principle of “one person, one vote”. Legislative-led redistricting took on a new level of political targeting and incumbent protection. It became a precision science post 2000 with advanced technology tools and centralized voter databases.

Today no new democracy would consider giving sitting legislatures the power over redistricting. In fact in a recent study of 60 democracies that divide jurisdictions into districts, the United States and France are the only democracies that let legislators draw their own districts. The other countries who use single winner districts to elect their primary representative body have switched to independent, non-partisan commissions to draw voting district lines – including England, Canada and Australia.

Nonpartisan Redistricting the U.S.

Nonpartisan redistricting has a foothold in the U.S. Voters in Arizona and California passed ballot measures taking away redistricting power from the legislature and establishing nonpartisan redistricting commissions. Iowa does something similar. It has an independent commission that draws a set of maps based on nonpartisan criteria that the legislature must choose from.

Redistricting is inherently challenging. While not perfect, nonpartisan commissions have worked better to put the interests of voters before incumbent legislators, operating with more public support and acceptance. The federal courts have a growing preference to get partisanship out of the redistricting process. In the last two years the Supreme Court rejected two high profile partisan challenges designed to dismantle Arizona’s voter-backed commission and return control to the legislature. This year federal courts sent partisan driven maps North Carolina and Texas back to the drawing boards. In Wisconsin, a court condemned districts it said primarily designed to artificially advantage the Republican party. For the first time they cited evidence from an analysis using a newly developed mathematical measurement of partisanship proof.

Bipartisan Commissions

Five other states, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Jersey, and Washington, use bipartisan commissions. They have equal numbers appointed by the two major parties that then jointly choose another member to act as a deciding vote. This does prevent the party in power taking all the spoils, but it still has the two parties – not voters – driving the process.

2020 and Beyond

Commissions can’t solve all the inherent challenges of redistricting done to equalize district population after the decennial census.

But one choice is clear. It is time to remove the power of drawing election districts from sitting legislators to an independent, nonpartisan body. This seems the minimum standard for any democratic or republican form of government. Public trust and confidence in government can no longer tolerate allowing sitting legislators to choose their voters, where even with good intentions, the driving criteria is self-protection or fixing the outcome to favor the party in power.

Create independent nonpartisan commissions such as those used in Arizona, California, and, under Iowa and other advanced democracies. Typically using nonpartisan voter approved criteria where districts must:

- Comply with the U.S. Constitution and the Voting Rights Act

- Be contiguous so that all parts of the district are connected to each other.

- Respect the boundaries of cities, counties, and neighborhoods, as well as “communities of common interest” (such as keeping a rural population together)

- Promote political competition that does not favor or discriminate against any candidate (incumbent or challenger) or political party.Learn more:

What is Gerrymandering, Andrew Prokop, VOX – here

Redistricting, National Conference on State Legislators (NCSL) – here

Comparative Redistricting in Perspective, Lisa Handley and Bernard Grofman, eds. Oxford University Press, 2008 – here