Updated on 12/21/20

If one good thing can be said for 2020, it would be that every component of America’s election system — from the local level to the state Electoral College certifications — worked exactly the way they were supposed to.

Millions of Americans signed up as poll workers for the very first time; voters took advantage of expanded absentee ballot access to vote early in numbers that were previously unfathomable; and US cyber warfighters worked tirelessly to deliver the most secure election in US history.

In a nutshell, the system worked.

But like any operating system, our democracy functions at its best when we, the users, are keeping up with system updates that improve and further secure the fundamentals of the process. And if there’s one system update that’s sure to be talked about every four years, it’s the Electoral College.

Five times in our history, the Electoral College has elected a president that lost the national popular vote. This year, but for a few thousand votes, the 2020 election came within an historical hair of doing the same. A change of a mere 0.03% (39,000 votes) in four states – Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, and Wisconsin would have elected the person trailing by a record million votes.

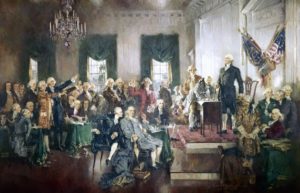

Questioning the wisdom of the U.S. Constitution’s framers is a healthy and essential act within the ongoing experiment that is American democracy. More so the last minute constitutional compromise principally forged to get slaveholder states to sign the constitution. Is it time to do what all 50 states and every other democracy with direct elections for its chief of state does – elect the president through the popular vote?

Where Did It Come From

The Electoral College emerged as one of many compromises designed to get all 13 original states to sign the Constitution in the transition from monarchy to a fledgling republic. One of the most persistent myths is that it was meant to help small states. James Madison, architect and chief lobbyist for the constitution, made it clear then that its roots lie in fact not to protect “small states” but was one of several compromises between slaveholder states and free states. Madison said “states were divided into different interests not by their difference of size, but by other circumstances; the most material of which resulted partly from climate, but principally from [the effects of] their having or not having slaves.”

The Electoral College doubled down on a prior concession, the “rule”. The rule allowed states to partially count non-voting slaves in order to boost the census number that would determine how many Congressional districts and therefore electors each state ended up with. Thus in the 1800 census, the state of Pennsylvania had 10% more free persons then the largest of slave states, Virginia, yet it ended up with 20% fewer electoral votes. With both the Electoral College and three-fifths rule, Virginia came up the big winner. As one consequence, a slave-holding Virginian won the presidency in the first eight of nine presidential elections.

On paper, small states appear to get a small boost from two electors they get for each senator. In reality, they are sidelined like any other non-battleground state. Consider the small states with only one Congressional district today – Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming. None were swing states in 2020, nor were they on the radar of presidential campaigns. In any case, why should some states and some voters get a special advantage in the election for the president who is meant to represent every one? The Senate was created to address needs of small states, as were a host of rights and protections all states share. That was the view of two small bi-partisan small state senators, Langer of North Dakota and Pastore of Rhode Island who led an effort to move to the popular vote in the 1950’s.

Beyond conceding slaveholder states an artificial advantage, the drafting of the constitution reflected uncertainty about turning over the outcome of the presidential election to a popular vote. While Madison and others favored the popular vote, some worried that with the great distances and slow or lack of communications of the era that voters couldn’t learn enough about the candidates to make an informed decision. Even with these hesitations, it is important to give them credit for taking the initial step of creating a popular election for the Congress. That was a bold move by historical standards, albeit in the context of a very limited franchise. The Electoral College only served to further incentivize keeping the franchise limited, as it still does today, especially in swing states where the stakes are high and fights over voter access continue.

Distorted democracy: Divided red and blue, battleground or sidelined

Having a national election decided by a small number of swing states rather the general population was problematic from the beginning. Over time it has divided states and voters into two tiers. The much contested swing states. And the rest of the country which is taken for granted. The irrelevance of most states – red and blue alike – has helped to drive bi-partisan support for reform over the years. Votes and voters are devalued by where they live in contradiction to democracy’s most fundamental principle of one person, one vote affirmed as recently as 2015 by a unanimous Supreme Court.

36 states and nearly 2/3s of voters on the sidelines

Instead of a national election we have a presidential contest focused on the outcomes and voter preferences of a subset of swing states. This year it left a large majority of the country’s 239 million eligible voters residing in non-battleground states as spectators and outsiders. Most Americans watched ads aimed at boarding states. Campaign volunteers skipped their local contests to take weekends away from their state to travel to ones that decided the bigger prize. As a nation, it spent a week following the results of a handful of swing states, and wondering whether the week long late count of mail ballots in states like Pennsylvania and Michigan as opposed to a Florida which counted its mail ballots first would tip the balance.

All money and attention go to a handful of states

Campaigns target all their money and attention to a few states. Consider this past election. Presidential campaigns and allied groups dropped more than $1 billion in political advertising spending in just 13 states. Furthermore, 204 of the 212 general election campaign events held in 2020 by major party presidential or vice presidential candidates took place in 12 states. The presidential election turns out to be a party to which most of us weren’t welcome, with our usefulness extending only so far as to ratify our state’s likely results and watch the real contest unfold on TV or online.

Grassroots democracy sacrificed

Through this process, we lose the essence of democracy – neighbor to neighbor, peer to peer politics. We miss the chance to fully engage in elections as a voter or campaigner in our own backyard, and to have local media focus on our local races or ballot measures as well as national trends. We miss the incentive to start a conversation with a neighbor or friend regardless of where they live.

Our nation’s newest voters lose the most. Campaigns focus their resources and voter contacts on likely voters and swing states. This concentration of competition within a few states is one reason more than half of Americans report never being personally contacted by a major campaign about voting. For 18-35 year olds it jumps to three of four young people never being contacted.

Divided red and blue

The Electoral College drives another source of civic polarization in an election decided by states rather than the nation as a whole – the division of red and blue states. This is something our farmers could not have predicted, nor did they have time to concern themselves with this possibility under the weight of war debt and a constitution to ratify. Yet, these divisions persist between election years. We form opinions about various states and their inhabitants, without considering the diversity of views that exist in any state. The colors have become “a proxy for all the differences in values and lifestyle that seemed to be cleaving the country into warring tribes.” A focus on state voter turnout, rather than state partisanship, might make for a healthier civic exercise, harnessing the citizenship benefits from active and informed participation in all spheres.

Votes don’t really count

Finally, people living in non-battleground states have come to learn that their vote really does not matter, and that has a very unfortunate impact on voter turnout. Voter turnout in non-battleground states is on average 5-8 percentage points lower than in battleground states. If we want to foster a more engaged electorate – in every state, in every county, and in every precinct – then we should send a clear message that the vote of every citizen matters, regardless of where they live.

National Popular Vote

Pennsylvania’s James Wilson – a major force behind the Constitution and one of six chosen by Washington for the country’s first Supreme Court -proposed the presidency be decided by popular vote. It became clear that wouldn’t work for slaveholder states or those that favored giving state legislatures a larger role in choosing the president.

Early on more than half the members of Congress saw the need for the Electoral College to better reflect the popular vote. One early idea was to choose electors by congressional districts. While Maine and Nebraska still use a version of this, it was agreed the results were problematic given the likelihood of gerrymandered districts that even in the 1800’s created distorted results.

If the idea is to keep the Electoral College, a more promising way to represent the popular vote as proposed early on would be to allocate electors proportionally within each state rather than on a winner-take-all method. In other words make every state competitive and give every voter in every state a meaningful vote.

The popular vote is still the most discussed path to move forward. As noted, it is the standard used by all 50 states for governor and every other election, the same way it is for every democracy that directly elects its top leader.

Why the popular vote or a proportional allocation deserve attention is that things have changed since 1787. Information disseminates everywhere and through multiple channels. It’s possible now in a way that it wasn’t until the 20th century to bring the nation together in an election where all votes count. There’s a greater incentive for people, campaigns and civic organizations to engage with neighbors, friends and voters locally and across states where engagement, education and democracy really happens.

Some worry that less populated areas will be passed over or big cities will dominate. As if being a resident of a city or populated area means your vote should count less.

The reality is that the large majority of Americans live in suburbs or rural areas. All voters of every kind of political leaning who must be appealed to. Compared to what happens now, campaigns would have to compete in far more media markets both large and small in all parts of the country. America’s largest 50 cities only represent 15% of the U.S. population.

How do we replace the Electoral College and can it happen?

The longer answer can be largely found in the new book by esteemed historian and author on the history of the vote, Alex Keyssar: Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College.

A shorter answer is that it will likely come by a constitutional amendment. The main way to add an amendment is to look at how all the others were passed. First as a resolution by a two-thirds vote in both the House and Senate or. Then ratified by three-quarters (38) of state legislatures.

This is not easy. Keyssar reminds us that it can happen. In 1969 it almost did. Led by Indiana Senator Birch Bayh with bi-partisan support, the national popular vote won by an overwhelming margin in the House and majority support in the Senate. A last minute filibuster by a few senators stopped it. Had it passed Congress, current events gave it a reasonable chance of approval in states.

Article Two of the US Constitution provides another route. It is based on the power vested in states to instruct how their Electoral College electors are appointed. Article two says each state shall appoint, “in such manner as the Legislature thereof may direct” the presidential electors allotted to them. Therefore State legislatures are free to select electors based on the outcome of the national popular vote. If enough states whose combined electoral votes add up to 270 or more do so, then the president will effectively be chosen by the popular vote.

The National Popular Vote organization and its civic allies are pursuing this route. It has gained bi-partisan support of constitutional scholars, elected officials and nonpartisan civic organizations. It has passed in Republican and Democratic led legislative bodies in 33 legislative chambers in 22 states. To date the legislatures of 15 states (for more since 2016)representing 196 electoral votes have voted to join what is called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, an agreement to award all their respective electoral votes to whichever presidential candidate wins the overall popular vote. Inter-state compacts can require Congressional approval. Views differ on whether it applies here. Either way, the leading supporters of the National Popular Vote have made it clear they will seek Congressional approval to forge a national consensus.

That national consensus may be a popular vote. Or updating the Electoral College to allocate electors proportionally instead winner-take all.

The Challenge Ahead

It won’t be easy. With two hundred years of inertia and time to build up myths of why the Electoral College even exists, it’s a challenge.

Looking back to 1787an indirect election may have made some sense as a bridge between colony and free nation. But the standard and expectations of democracy in the U.S. have changed. For decades a majority of Americans across state lines or partisanship lines have opposed the Electoral College. The last and only meaningful upgrade was the 12th amendment in 1804 to have the vice president and president run on the same ticket. The time for change is long overdue. It was flawed then, it is flawed now. Divisive then and divisive now.

If our founders were with us on election night watching CNN’s iconic red and blue map to see 36 of 50 states and two-thirds of the U.S. population left on the sidelines, they might well agree it’s time as well.

Madison would have. The Electoral College was always a compromise for him. Hamilton would too. He mainly wanted to leave the selection of the president to a small august group of legislative appointed “electors” rather than to either Congress or to the public. His elite model never happened. Who the electors were and their qualifications quickly as electors whoever they are must support the plurality winner of their state.

Thomas Jefferson perhaps said it best.

“(N)o society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law. The earth belongs always to the living generation. They may manage it then, and what proceeds from it, as they please, during their usufruct [time of use]. They are masters too of their own persons, and consequently may govern them as they please. But persons and property make the sum of the objects of government. The constitution and the laws of their predecessors extinguished then in their natural course with those who gave them being. This could preserve that being till it ceased to be itself, and no longer. Every constitution then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19 years [each generation]. If it be enforced longer, it is an act of force, and not of right.” Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, 6 Sept. 1789, Papers 15:392—97